June 22, 2004

The time I played at Sweetwaters 1999

Here's one from the archives - I found this on an old floppy disc from about four years ago. It was meant to be a magazine article but never got published...

The term “noise” is much maligned in music, especially when used by insensitive neighbours/parents/flatmates. But there are whole musical subcultures and genres that thrive on it. As a teenager, falling in love with music for the first time I had the natural urge to share this love with the whole household. This never went particularly well, but as my tastes developed, my responses to the inevitable turn-that-noise-down had to make a strategic retreat from a petulant “it’s not noise (you are)” to a sheepish “but it’s good noise”.

To the connoisseur, there are fine distinctions between everything from Anti-Pop to Pigfuck, and everything in between. What the non-noisenik doesn’t recognise is that all sound is noise, including all music. The Oxford Dictionary defines noise as “a sound, especially a loud or undesired one”. So Mozart is noise, especially at high volume and when you’re not in the mood.

By contrast the dictionary definition of music as “the art of combining vocal or instrumental sounds (or both) to produce beauty of form, harmony, and expression of emotion” is very narrow. If it isn’t beautiful, harmonious, and expressive, it can’t be music.

Rather than attacking narrow preconceived ideas of what is music head-on, like the avant-garde or punk, noise side steps and subverts these ideas. Melody, harmony, and even rhythm are simply not that important, if they exist at all. The important thing is sounds and tone.

Generally noise can be used in two ways. The first is as a colour to spice up otherwise conventional music. The second way is to make noise the basis of a style. This is the hardcore approach. Like hardcore punk, which does away with any extraneous instrumentals to emphasise the rock structure, and free improvisation, which does away with any extraneous structure to emphasise the instrumentals, free noise does away with anything remotely musical to emphasise the sound.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

These concepts were not discussed in detail prior to the debut performance of the Bird & Truck Collision. The instructions given for our half hour were that a) no lyrics, recognisable melodies, or steady beats were permitted, and b) that the set would consist of a “quiet half” and a “loud half”. The transition from quiet to loud was to be signalled by the sound of a lawnmower starting on the four-track recordings we were playing along with. I asked Paul whether the change should be sudden or gradual and the question seemed to throw him a bit. The score didn’t specify.

I had spent the day in the back of a van, driving up to Auckland for Sweetwaters. I happened to have my electric guitar, a cheapshit Stratocaster-imitation, with me because I knew a guy who knew a guy who had a gig lined up at Sweetwaters. I had heard some of an album by this person, entitled Heaven on Earth. It consisted of complex high-pitched twittering sounds, interspersed with silvery chimings. It made me think of the seaside for some reason, though later when I played a copy to a friend he said it reminded him of rush-hour traffic.

I met Paul for the first time on the Friday the festival was starting. He said “so you want to be in the band”. I was probably wondering if I’d be asked for an impromptu audition (no I can’t play “Stairway to Heaven” sorry, uh…), but no I was in just like that. We discussed the plan for the set. This didn’t take long, and I got back in the van for a ride to the festival grounds.

The Sweetwaters site was pretty impressive to my festival-inexperienced eyes. I don’t think I ever did explore it all. It wasn’t until after the thing was over that I found out what a “failure” it was. In retrospect the not-quite teeming crowds and the cancellations of some key acts were obvious clues. But Sweetwaters was not a failed festival, only a failed business venture. An impression I did get was that people weren’t sure how much of a hippie thing this was – was it Woodstock or wasn’t it? And if so, how ironic to be? Remember the 90s; remember irony?

On Saturday morning, the members of the Bird & Truck Collision assembled to set up for our contribution to the festival. We were first on, so there were a lot of people running around setting things up. As I hadn’t met most of my bandmates, the way to tell them apart from the crew was that crew members kept running up to me wit technical questions, such as how many microphones we needed. I had to redirect all enquiries to Paul, even basic ones like “how many people are there in your group?” The answer to both questions was probably “how many can we have?”

Paul himself was busy setting up his equipment, which included a small keyboard, a large synthesiser unit, an odd-shaped bass guitar to trigger it, and his own mixing board. The synthesiser had just had a load of water dumped on it by the flapping tarpaulin strapped to the stage rig, which was a worrying start. The next time I saw Paul play, several months later, someone in the audience threw a handful of whipped cream at his gear.

The set began with the pre-recorded sound of cicadas blending with the backwards-chirping sounds from the synthesiser, which I had heard on Heaven on Earth. A drummer, one of Paul’s fellow veterans from the Sunset Coast Big Band in Waiuku, was quietly brushing and doing rolls on a single snare drum. I played a couple of staccato guitar notes and chords here and there.

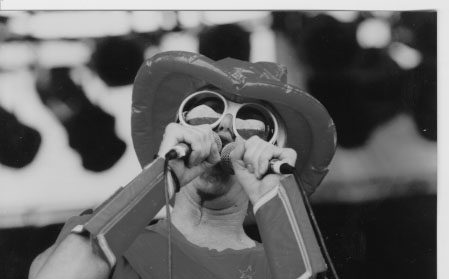

The quiet half of the set had its own slow rhythm, the sounds rising and falling, with swells in volume. Things gradually became more active. An audience began to form. Vocalists started singing wordlessly. The guy in the bright red cape and hat, the Reverend Stinkfinger, started running around more. He had a bed of nails with him, and explored its possibilities as a prop. He also started climbing the scaffolding at the side of the stage, and was dragged down by security. I was playing my guitar with a knife and fork.

The sound of a lawnmower starting began on the tape. Paul was nodding at everyone. I started turning all the control knobs I could find up to ten. The amp started feeding back madly. The drumming intensified. The vocalists were yelling. A guy with a microphone ran around the stage, sampling sounds and throwing them back into the mix. I could no longer hear Paul – I found out later that the sound engineers had seen him put on headphones, and dropped him out of the monitors, so no-one else on stage could hear him. My guitar was so overdriven that I could play something and not be able to hear it make a difference to the roaring. I jumped around as much as I could, now quite possessed by the sound. Noise can do that. Unlike traditional music, which has many techniques by which to manipulate emotions, noise shuts out emotions and thought. This is the same goal Buddhists have in meditating.

All too soon it was over, our half-hour almost up. The stage manager was making cutting gestures across his throat. The sounds died away, reality came back. Some of the audience wore puzzled frowns, others were grinning. There is a rumour that one woman had an orgasm during our set (though even if this is true, there may not have been a causal relationship). One guy told us later on that we had been “too rock & roll”; others noted that it was the lawnmower sound, which seemed to start everything up. The Paua Fritters were the next band on; I have no idea what they thought of their opening act. None of us know what we sounded like, as the guys who were supposed to record the set failed to turn up. What I heard on stage is different from what anyone else on stage heard, and the audience heard something else again. Video footage was taken, but is now locked away in the vaults, as Sweetwaters seems to be something the organisers would rather forget.

I learned a couple of interesting things later on. The Reverend Stinkfinger was punk veteran and filmmaker Brent Hayward. I was later made an honorary member of his fan club. Paul turned out to also be from my hometown of New Plymouth, and in fact had lived on the same street before his eight-year stay in Houston, Texas. The official Sweetwaters Artist Passes got us backstage at the main stage, which with a bar and porcelain toilets was somewhat more luxurious than the fenced compound with Portaloos behind the NZ Stage. When Shihad played we stood at the back of the stage and looked out over the crowd. Neil Finn was there, but I had nothing to say to him. We had reached the lower rungs of pop culture.

Brent Hayward, aka The Reverend Stinkfinger. Chris Knox compared my first album Scratched Surface to him - interesting coincidence since I'd unwittingly played with the guy. Paul also gave me a lot of help with recording and playing on my second album The Marion Flow.

http://fiffdimension.tripod.com

Posted by fiffdimension at June 22, 2004 01:48 PM | TrackBackHey I was at sweetwaters and saw a band that was 'way rock and roll' - could have been you guys but it feels like so long ago....

And i will never forget the performance Chris Knox gave at Sweetwaters - stirling!

Posted by: cal at June 23, 2004 08:54 AM"Neil Finn was there, but I had nothing to say to him."

Heh...

Posted by: Sister Novena at June 23, 2004 10:57 AMyou saw pere ubu surely?

they're the reason i blagged the 14th redundant assistant 3 day pass on the free east timor stall.

Must've worked tho.